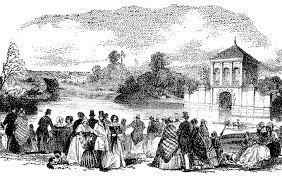

Having returned from the Chelsea Flower Show, I must admit it just gets better every year. Cleve West’s sunken Roman garden won best in show, Diarmuid Gavin theatrics stopped traffic, and my personal favorite garden was Luciano Guibbilei’s for his serene and elegant Laurent Perrier garden.

Show gardens (at Chelsea) are proposed to the Royal Horticultural Society almost a year before the actual show and are either accepted or denied. For sheer uniqueness there was the artisanal Hae-Woo-Soo garden, which I led on about last month. The Hae Woo So garden was one that stretched the boundaries of the “British proper.” One person on the acceptance committee mentioned to me “we knew it would either be extraordinary or be an embarrassment.” Thankfully, the garden was exemplary and honored with a gold medal.

According to Jihae Hwang, who designed the garden, this conceptual landscape refers to a place where you “empty your mind.” According to ancient Korean tradition visiting the lavatory (the trip to it) is traditionally regarded as a cathartic experience, a way to spiritually cleanse one’s mind and reconnect with nature through a “natural cycle” -- the physical act that accompanies it. The focal point of the garden is an elegant wooden dunny (an outhouse). The lintel is low, forcing one to bow as you enter, humbling oneself. Typically the wooden building (the latrine) serves a dual purpose in that the human waste is left to ferment, creating fertilizer.

Stipa tenuissima, Paeonia lactiflora and Lonicera japonica embrace a stone wall

A washbasin filled with rainwater to cleanse one's hands

In romantic disorder, plants are arranged along the path to “the throne.” Small, highly scented lilacs, Syringa wolfii and Syringa dilatata and Lonicera japonica (Honeysuckle) aid in perfuming the air surrounding the latrine.

**all photos ©Todd Haiman 2014