A. J. Downing (1815-1852) popularized landscape gardening among America’s growing middle and upper middle classes through his aesthetic sensibilities. He wrote the first American treatise on landscape gardening -- A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening, Adapted to North America

(1841), which established him as a national authority on that subject and went through numerous editions (the last was printed in 1921). Following British models, he categorized landscape design styles as “The Beautiful” (calm and serene) and “The Picturesque” (dramatic), with the style to be determined by the existing landscape context. He was the first great American exponent of the English or natural school of landscape gardening as opposed to the Italian, Dutch and French artificial schools.

He was an advocate for the creation of public parks in America and the health value of interaction with the natural world. He stood for the simple, natural, and permanent as opposed to the complex, artificial and ephemeral.

As editor of the Horticulturist and the country's leading practitioner and author, he promoted a national style of landscape gardening that broke away from European precedents and standards. Like other writers and artists, Downing responded to the intensifying demand in the nineteenth century for a recognizably American cultural expression.

Lindley's Horticulture by A.J. Downing. Originally published 1852. (Author's copy)

Believing that architecture, too, needed to conform to site character, he brought architect Calvert Vaux from England in 1850 to assist him in his practice, including the design of Matthew Vassar’s estate, “Springside”, at Poughkeepsie, NY. (Six years later, Vaux named his second child Downing Vaux in tribute to his mentor.) Frederick Law Olmsted, Sr., a friend and colleague, was one of the many visitors whom Downing entertained at his villa on the Hudson River at Newburgh, NY. Downing’s influence is strongly reflected in the Olmsted and Vaux design for Central Park,

Downing spent his life in the spectacular natural setting of the Hudson River valley. Through his professional practice, travels, reading, and extensive correspondence, he gradually became aware of the individual and collective needs that he served. Landscape gardening, Downing came to feel, had to respect not only a client's desires and means, but also the nation's republican values of moderation, simplicity, and civic responsibility.

While influenced by European, especially British, writers Archibald Alison, Uvedale Price, Humphrey Repton and John Claudius Loudon) he recognized that America should not emulate European gardening styles. First, Americans should make use of American material, hence his interest in all native American species. Second, America, was not aristocratic and should celebrate it republicanism, hence his designs for middle class and a few lower class cottages and gardens in his architectural work. He also understood that his country was young and still rapidly expanding and that horticulture could serve as a way to attach the white settlers to their new home. Finally, he recognized two important developments in horticulture: the rise of scientific inquiries and the development of a class of professional landscape designers/gardeners who were artisans, not artists.

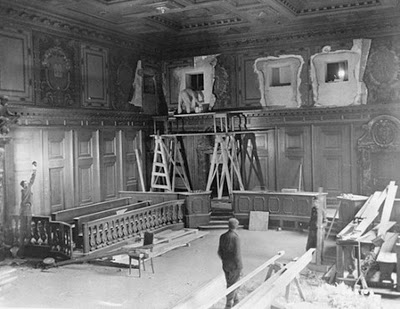

Recognized as the foremost U.S. landscape designer of his day, he was commissioned in 1851 to lay out the grounds for the Capitol, the White House, and the Smithsonian Institution. His death at 36 in a steamboat accident prevented him from seeing his plans to completion.

An urn at the Smithsonian Institution commemorates his work. (Images ©Smithsonian Institute)

Downing is imminently responsible for Central Park. He called for and politicked for the creation of a great park in New York City worthy of the city. If it were not for his untimely death he presumably would have been chosen to design Central Park. Instead, his suddenly uncoupled partner Calvert Vaux would then join with Frederick Law Olmsted in the creation of countless notable landscapes.