Alexander Pope said ‘‘all gardening is landscape-painting.’’ He laid the widely agreed principles of landscape architecture and design.

Read MoreHumphrey Repton

THE FATHER OF LANDSCAPE DESIGN IN THE UNITED STATES

A. J. Downing (1815-1852) popularized landscape gardening among America’s growing middle and upper middle classes through his aesthetic sensibilities. He wrote the first American treatise on landscape gardening -- A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening, Adapted to North America

(1841), which established him as a national authority on that subject and went through numerous editions (the last was printed in 1921). Following British models, he categorized landscape design styles as “The Beautiful” (calm and serene) and “The Picturesque” (dramatic), with the style to be determined by the existing landscape context. He was the first great American exponent of the English or natural school of landscape gardening as opposed to the Italian, Dutch and French artificial schools.

He was an advocate for the creation of public parks in America and the health value of interaction with the natural world. He stood for the simple, natural, and permanent as opposed to the complex, artificial and ephemeral.

As editor of the Horticulturist and the country's leading practitioner and author, he promoted a national style of landscape gardening that broke away from European precedents and standards. Like other writers and artists, Downing responded to the intensifying demand in the nineteenth century for a recognizably American cultural expression.

Lindley's Horticulture by A.J. Downing. Originally published 1852. (Author's copy)

Believing that architecture, too, needed to conform to site character, he brought architect Calvert Vaux from England in 1850 to assist him in his practice, including the design of Matthew Vassar’s estate, “Springside”, at Poughkeepsie, NY. (Six years later, Vaux named his second child Downing Vaux in tribute to his mentor.) Frederick Law Olmsted, Sr., a friend and colleague, was one of the many visitors whom Downing entertained at his villa on the Hudson River at Newburgh, NY. Downing’s influence is strongly reflected in the Olmsted and Vaux design for Central Park,

Downing spent his life in the spectacular natural setting of the Hudson River valley. Through his professional practice, travels, reading, and extensive correspondence, he gradually became aware of the individual and collective needs that he served. Landscape gardening, Downing came to feel, had to respect not only a client's desires and means, but also the nation's republican values of moderation, simplicity, and civic responsibility.

While influenced by European, especially British, writers Archibald Alison, Uvedale Price, Humphrey Repton and John Claudius Loudon) he recognized that America should not emulate European gardening styles. First, Americans should make use of American material, hence his interest in all native American species. Second, America, was not aristocratic and should celebrate it republicanism, hence his designs for middle class and a few lower class cottages and gardens in his architectural work. He also understood that his country was young and still rapidly expanding and that horticulture could serve as a way to attach the white settlers to their new home. Finally, he recognized two important developments in horticulture: the rise of scientific inquiries and the development of a class of professional landscape designers/gardeners who were artisans, not artists.

Recognized as the foremost U.S. landscape designer of his day, he was commissioned in 1851 to lay out the grounds for the Capitol, the White House, and the Smithsonian Institution. His death at 36 in a steamboat accident prevented him from seeing his plans to completion.

An urn at the Smithsonian Institution commemorates his work. (Images ©Smithsonian Institute)

Downing is imminently responsible for Central Park. He called for and politicked for the creation of a great park in New York City worthy of the city. If it were not for his untimely death he presumably would have been chosen to design Central Park. Instead, his suddenly uncoupled partner Calvert Vaux would then join with Frederick Law Olmsted in the creation of countless notable landscapes.

WILLIAM GILPIN AND THE PICTURESQUE

An aesthetic revolution that occurred in Britain in the eighteenth century revolved around several main theories, but the most important theory that applied to landscape was that of “the Picturesque”, most often associated with the writings of William Gilpin.

Originally an ordained minister in the Church of England, he began writing these popular treatises as a means to raise funds for his school.

The picturesque emphasized roughness over smoothness, boldness over elegance, and variety over uniformity. These concepts were initially influential in painting and then to landscape design.

Gilpin’s defining ideas influenced friends such as Horace Walpole and the royal family, including King George. While the wealthy could afford to indulge themselves with the Grand Tour (the traditional travel of Europe undertaken by upper-class European society), appreciating and purchasing great paintings and ultimately contracting landscape designers such as Lancelot “Capability” Brown and Humphrey Repton, Gilpin was instrumental in influencing the rising upper-middle, the minor gentry and tradesmen. By leading tours through the countryside and publishing aquatint landscape prints he created an aristocratic taste level among the rest of the public.

His concept of "the Picturesque," which first appeared in the Essay on Prints as an additional concept to "sublime" and "beautiful," was intended to formulate an appreciation for landscape in the paintings of Nicolas Poussin or Claude Lorrain.

Essay II: On Picturesque Travel is a manual for appreciating travel and sketching the landscape as a way to preserve the beauty in one’s mind.

Meanwhile, Jane Austin’s novels (Sense and Sensibility, Pride and Prejudice,

Mansfield Park, Northanger Abbey and Emma) used the picturesque as a backdrop. While a fan of her writings illuminated his concepts to a larger audience, although at time it has been suggested that she satirized him.

Throughout each of these novels the landscape holds a defining and center-stage role. Her heroines are brought up in well-established homes and were receptive to the matters and opinions of current taste. Her novels reflect the social and landscape history of England.

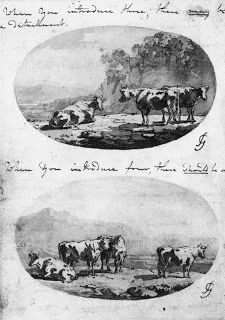

Her novels assimilate and promote the ideals of Gilpin, yet also satirize them. In one of Gilpin’s publications he provided instructions for the groupings of cows in a pasture – “to unite three and remove the fourth.” Many landscape painters followed suit. But, in Pride and Prejudice, one character refuses to join in a stroll with the teasing observation, "You are charmingly group'd, and...The picturesque would be spoilt by admitting a fourth."

William Gilpin illustrations of how to group cows Bodelian Library In Sense and Sensibility, one character is dismayed that another is apparently ignorant on picturesque theory and promptly instructs him… “ I shall call the hills steep, which ought to be bold; surfaces strange and uncouth, which ought to be irregular and rugged: and distant objects out of sight, which ought only to be indistinct through the sift medium of a hazy atmosphere. It unites beauty and utility – and I dare say it is a picturesque one too.” When Elinor Dashwood teases her sister about her passion for “dead leaves” she responds by reminding Elinor that it is her appreciation of the picturesque.